Tao Te Ching

Robert Beer

Mahasiddha (གྲུབ་ཐོབ་ཆེན་པོ) Lineage

The Mahasiddha tradition of India and Tibet parallels the Trickster archetype in other cultures; the fearless disregard for all conventions, social concepts, customs, and blind beliefs. Spiritual anarchists, anti-establishment rebels, and tantric legend; they often commingled with the lowest rungs of the social structure - criminals, drug addicts, prostitutes, and the insane while appearing to their students - often high class politicians, merchants, and teachers - as the most common and disrespected members of society. These Mahasiddhas reacted against the rigid caste rules, the ritual and spiritual dogmatism, and the arid scholasticism of their time transforming their society and creating what historians describe as “the most magnificent achievement of India’s cultural history.” Representing remarkable diversity and coming from every walk of life, family background, and professions from king to housewife, from priest to prostitute, from poet to farmer, and from thief to craftsman; they demonstrate the potential for all of us to become true, to realize the depths of compassion, the heights of wisdom, and the Buddha’s realization.

People (59)

Dharmapa thos pa’i shes rab bya ba

915

“The Perpetual Student” — Mahasiddha #36

Dharmapa lived his life as a scholar, a professor, a pandita. He spent his entire life studying and teaching but gave little time or attention to meditation or other practices. He didn't become aware of the gap this left in his awareness until he was old and blind. He realized his need for a teacher but was no longer in a position to fine one. A dakini appeared in a dream however, and taught him the difference between analytical understanding and realization. He showed Dharmapa how he could—like a blacksmith melting pieces of iron into a single ingot—melt all the disparate strands of his knowledge into a unified experience of true mind and wisdom.

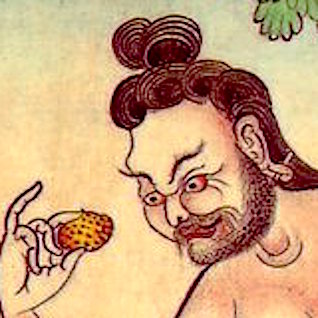

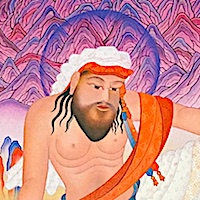

Nagarjuna नागर्जुन

c. 150-250 CE

Considered the most important Buddhist philosopher after the historical Buddha, Nāgārjuna founded the “middle way” Madhyamaka school, developed the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, the concept of śūnyatā, or "emptiness," the ultimate and relative “Two Truths.” He also served as the head of Nālandā University and as the "father of iatrochemistry" practiced Ayurveda medicine. An important factor in Buddhism’s spread to Tibet, China, Japan and other Asian countries, his teachings represent the pinnacle of philosophical insight and wisdom.

Nagabodhi ནཱ་ག་བོ་དྷི། (The Red-Horned Thief)

c. 180-265

Nagabodhi—a Brahmin turned thief—decided to rob the mahasiddha, Nagarjuna. Before he could do anything though, a golden chalice flew out a door and landed in his hands. He returned and something similar happened with a golden plate. At his third return, all of Nagarjuna’s wealth came to him as well as an invitation to eat and talk with the famous sage. Nagarjuna taught Nagabodhi meditation and gave him a houseful of precious treasures. Nagabodhi’s attachment and fixation on these however manifested as a large and painful horn growing out of the top of his head. Further instruction and practice enabled him to finally see through his delusion to the extent that he became Nagarguna’s successor. Mahasiddha #76

Āryadeva འཕགས་པ་ལྷ། (Kannadeva)

3rd C. CE

Born a king, Aryadeva became teacher to 1000 monks, a Mahasiddha, abbot of Nalanda University, disciple/teacher of Nagarjuna, 15th patriarch of Chan Buddhism, medicine doctor monk, and cofounder of the Mahayana school. One of “the six great commentators on the Buddha's teachings,” he wrote many important texts, exemplified in his path the progressive loss of a belief in a separate self, and remains a shining example of direct and complete realization.

Shantideva ཞི་བ་ལྷ།།། (Bhusuku, Śāntideva)

685 – 763 CE

Son of a king, Indian scientist, Buddhist monk, "The Great Poet," and unliked Nalanda University scholar known for not studying, practicing meditation or showing up for events; Shantideva was challenged by the university to give a talk as proof that he really belonged there but really as way of getting rid of him. Shocking the scholars and monks who wanted to expel him, he gave a talk that became the famous Bodhicaryavatara, The Way of the Bodhisattva or Entering the Path of Enlightenment. Leaving the University and following Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy, his teachings became a strong foundation for the Mahayana tradition. Mahasiddha #41

Saraha

8th century CE

Earliest Mahasiddha, founding father of the Buddhist Vajrayana and Mahamudra tradition; Saraha was expelled from a monastery for drinking alcohol, found a young low caste bride, became a maker of arrows, and went on to write the main Mahamudra meditation text and become a great yogi and master song writer. Like Lao Tzu, he followed the same “Inborn Natural Way” and began the lineage which descended through time to Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa, Milareapa and now to the Gyalwang Karmapa.

Kaṅkāripa ཀངྐཱ་རི་པ། (”The Lovelorn Widower”)

8th C. CE

Mahasiddha #7

A low caste householder happily married and filled with sensual pleasure, Kankaripa collapsed into despair when his beloved wife unexpectedly died. Confronted and asked by a wise teacher why he was letting himself grieve so much and wouldn’t let go of the corpse when “All life ends in death, every meeting ends in a parting;” he learned meditation practice, how to visualize his dead wife as a Dakini, attained ultimate realization, and became a wise, enlightened sage. Understanding how big as well as small “disasters” can become the most important, beneficial, life-changing events in our lives; this ordinary, uneducated man exemplifies transforming another affliction into spiritual path.

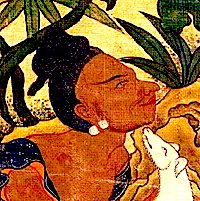

Lakshmincara ལཀྵྨཱིངྐ་རཱ།། (“The Princess of Crazy wisdom”)

c. 8th Century CE

Born into a royal family and pledged as a wife to the king of Ceylon, when Lakshmincara saw the king for the first time hunting and killing animals, she gave away her large dowry to the common people, pretended madness to stop the wedding, and moved to the charnal grounds to practice and realize enlightenment. She survived on food thrown out for dogs and took an untouchable latrine cleaner as attendant and first student. She became famous with many disciples. Her former fiancé’s father, the king Jalendra also wanted to become a disciple but she instead referred him to her student, the latrine sweeper who became his teacher. Mahasiddha #82

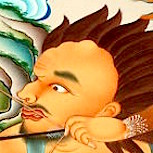

Śavaripa ཥ་ཝ་རི་པ། (Śabara, “The Hunter”)

8th – 9th C. CE

Mahasiddha #5

From the lowest wrung of untouchables and a wild, aboriginal tribe, the Śabaras; Shavaripa became a forefather of the Tibetan Kagyu lineage and a famous teacher. From a tradition known for crazed sexual passion, smoking marijuana, and drinking alcohol from a skull cup; he and his wife transformed their tradition into a potent symbol for tantric Buddhist practice. From a skilled and proud hunter, Shavaripa became a beacon of vegetarianism. Known as “Saraha the Younger” and a student of Nagarjuna, he transmuted aggression into loving kindness for all beings and through his disciple Maitipa transmitted this tradition to Marpa who brought it to Tibet.

Lilapa སྒེག་པ། (“Master of Play”)

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #2

“He Who Loved the Dance of Life,” Lilapa was a king who wanted to become enlightened but didn’t want to leave the luxury and privilege of his kingdom. A wandering yogin gave him practices he could do surrounded by his riches, power, musicians, and wives. He devotedly practiced, attained realization, and became famous for his philanthropy and kind goodness. Like Epicurus in the West, Lilapa taught and exemplified how spiritual realization doesn’t depend on asceticism, rigid discipline, and self-denial but harmonizes more with appreciation, cheerfulness and respect.

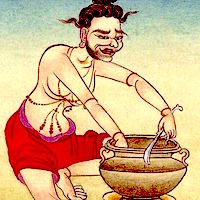

Lūipa ལཱུ་ཨི་པ། (“The Fish-Gut Eater” )

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #1

In the noble but uncommon tradition of the 1% voluntarily equalizing wealth, Luipa disdained his excessive riches and though born a king, like the Buddha he left his kingdom for a spiritual path. More than just his wealth though, Luipa’s teacher gave him a practice of abandoning his royal blood/Brahmin, food-purity culture prejudice by for 12 years eating only the fish guts normally intended only for dogs. This made him an untouchable and closed the door back to his former status and privilege. As a mendicant sage, he became an important teacher to many and passed into legend.

Bhadrapa

8th century CE

A “goody-two-shoes,” Brahmin purist intent on complete political correctness and purity; when the cleanliness obsessed and wealthy Bhadrapa met a homeless yogin he was repelled and cried out, “Unclean!” The teacher countered that physical form isn’t unclean, only the psychological corruption of body, speech, and mind. Bhadrapa realized his bigotry, that real purity means giving up ego-clinging and has nothing to do with following conventions and religious rules. He became a disciple, renounced his caste privileges and practices, cleaned latrines as his spiritual practice and became a great Mahasiddha himself.

Godhuripa གོ་དྷུ་རི་པ། (“The Bird-Catcher”)

700 – 800 CE

Mahasiddha #55

Godhuripa’s livelihood was based on killing birds. He knew this was not good and created bad karma for himself; but, he didn’t think he had a choice because this was all he knew how to do. A teacher challenged this opinion pointing out that selling his soul for material gain only made things worse in the long run. He gave Godhuripa a spiritual practice of listening to the birdsong not to find and kill the birds but to discover “the sound of silence,” the one taste and unity of sound and emptiness. He let all the birds go, gained direct perception of sound, and became a teacher with hundreds of students. Mahasiddha #55

Tantepa

8th century CE

Tantepa ཏངྟེ་པ། “The Compulsive Gambler (8th century CE) #33

A stereotypical gambler who lost all his money, lost all his credit, lost all his friends, lost all his self-respect but still couldn’t stop gambling even with the wise teacher he met who offered to show him a path away from his intense suffering; Tantepa was intrigued when this teacher agreed to show him a spiritual path based on his gambling experience instead of only moralizing and telling him to change. Instead of fighting against his strong feelings, his practice became looking directly into the experience of emptiness he had when losing, extending that perception to the worlds of sense, form and his own mind. This led to his realization that all thoughts and beliefs are equally empty and a new life as a teacher famous for his compassion and insight into the human failings of his students.

Vinapa

8th century CE

Only son of a King, so obsessed with music he would barely stop for food, Vinapa refused to learn about politics and leadership, would only listen to and play music. In a desperate attempt to win his attention, his parents found the great yogin Buddhapa to teach him. His attention was won but the master gave him a music meditation practice saying, “Free yourself of all duality between the sound itself and what your mind perceives. Without concept or judgement, contemplate only pure sound.” Vinapa became enlightened and a great Mahasiddha teaching and benefiting countless beings.

Kirapālapa ཀི་ར་པཱ་ལ་པ། (Kirapalapa, "The Repentant Conqueror")

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #73

A retelling of Ashoka’s story set in more recent times, Kilapa was a rich, powerful, and insatiable king obsessed with continually getting more wealth, power, and territory. When he personally confronts the horrors of war he completely changes and dedicates his life and kingdom to helping others, peace, education and poverty alleviation. His spiritual practice is distracted by the affairs of state until his guru gives him a visualization practice seeing his subjects as sacred beings and his kingdom as “the infinite emptiness of mind.” He then becomes a great siddha himself.

Catrapa ཙ་ཏྲ་པ། ("The Lucky Beggar")

750 – 850 CE

Mahasiddha #23

Catrapa while begging always carried a small dictionary that attracted a wise teacher who asked him about the book and then his life. This led to teachings and a practice of dissolving all concepts, prejudice, negative and moral conditioning, and a blending of action with perception into a deep, non-dual awareness of each everyday experience in life. Instead of teaching morals, ethics, and discipline; he exemplified and taught the crazy wisdom of wu wei, enlightened spontaneity based on direct, unfiltered realization. Mahasiddha #2

Sarvabhaksha སརྦ་བྷཀྵ། ( “The Glutton” )

late 8th, early 9th century

Mahasiddha #75

A born hungry, low caste man with an enormous appetite, Sarvabhaksha constantly dreamed about food, even after a huge feast. A chance meeting with the great siddha Saraha led to a vision of hungry ghosts—wretched wraiths with mouths like the eye of a needle and stomachs like an empty mountain—and a spiritual practice based on generosity and compassion. His insatiable desires shifted from food for himself to happiness for all sentient beings and he became a great teacher himself. His story demonstrates the the reality-changing power of visualization, both for the positive and the negative—on one hand the capacity of a Hitler to create a black magic hallucination creating the holocaust; on the other, positive visions like the American Dream, the Christian “Heaven on Earth”, and the Eastern Shambhala myths.

Ghaṇṭāpa གྷ་ཎྚཱ་པ། (“The Celibate Bell-Ringer”)

early 9th century

Mahasiddha #52

One of the earliest Kalacakra practitioners, founder of the Pancakrama Samvara lineage, Nalanda scholar, and guru to a king; Ghantapa became a symbol for appropriate action outside the confines of rigid ethics and morality, allegiance to personal insight over status quo strictures, and belief in the sense above the words. As a celibate monk, he saw through the chains of public and monastic opinion, desire for fame and acceptance, dissolved his vows, drank liquor, had sex, took on a consort, and had a child. His example inspired the people of his village and hearers of his stories during the centuries to dissolve their self-righteousness, prejudice, and sectarianism. Mahasiddha #52

Dhobīpa དྷོ་བཱི་པ། (“The Wise Washerman” )

806 – 906 CE

Mahasiddha #28

From a family of washermen in a country where purification and cleanliness were high spiritual values and people were expected to take ritual baths twice a day, Dhobipa spent his time washing clothes and cleaning things. A wandering, wise yogi visited him with a piece of coal and asked him to clean it, to take out the stain. Recognizing that the impossibility of cleaning coal by washing is like the impossibility of realizing wisdom with dogmatic belief, increasing goodness with materialistic intentions, or healing inner wounds with mindless ritual; Dhobipa went beyond convention and became a great teacher himself. Mahasiddha #28

Tantipa ཏནྟི་པ། ("The Senile Weaver")

1st half of 9th century

Mahasiddha #13

When he was 89 years old, Tantipa’s wife died and he became increasingly decrepit and senile. Becoming more and more of a liability to his weaving business and an embarrassment to his family, they built a hidden-away hut for him so they and visitors wouldn’t have to see or hear him. A passing-through Mahasiddhia, Jalandhara gave him teachings and practices to prepare for death and after many years of his silent meditation practice, he overcame the debilities of old age, attained the highest realization, became involved again in his cultural world even stopping the practice of animal sacrifice in his district. His life symbolizes and represents both the internal and external potentials of old age, the inspiration that any condition is fertile ground for enlightenment.

Campaka ཙ་མྤ་ཀ (“The Flower King”)

820 CE –

Mahasiddha #60

Extremely wealthy, powerful, caught up in pleasure, and sitting on a throne made from sweet-smelling flowers; Kampala met a wandering yogi. He tried to impress the sage with the splendors of his kingdom and the beauty of his flowers but the sage told him the truth, that his flowers smelled great but his body not so much, that his realm was wonderful but before long it and he would be gone. Realizing the superficiality and meaninglessness of his life, Kampala began a spiritual path but only shifted his physical materialism into spiritual materialism. Directed to focus his meditation on “the flower of pure reality,” he practiced and finally realized the empty essence of his mind. Mahasiddha #60

Medhini མེ་དྷི་ནཱི། (The Tired Farmer)

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #50

A low-born farmer working from early morning until late at night, Medhini decided to embark on a spiritual path but couldn’t get thoughts about farming out of his mind. His guru taught him how his thoughts about cultivating the earth could be understood, practiced, and applied to the cultivating of his own awareness. Having realized the non-duality of farming and realization, he discovered the unconditioned nature of reality and went on to teach and benefit countless students.

Chamaripa ཙཱ་མཱ་རི་པ། (Cāmāripa, “The Siddha Cobbler”)

840 – 940 CE

Mahasiddha #14

A poor cobbler in ancient India, Chamaripa worked long hours making and repairing shoes while he dreamed of a higher, more meaningful life. Disgusted with the emptiness of his life he begged teaching from a wandering teacher and began a practice of visualizing his work as meditation practice, his tools and materials as symbols for deep understandings. He discovered how the thread that tied his shoes together was like the thread of emptiness (shunyata) that connects a core enlightenment back through our graspings for fame, fortune, pleasure, and power. Mahasiddha #14

Ḍeṅgipa ཌེངྒི་པ། (“The Courtesan's Brahmin Slave”)

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #31

Brahmin minister to a king who left his wealth and status for a spiritual path, Ḍeṅgipa met his guru but because he had no appropriate gift to give offered his body as a slave. His guru then - to reduce his royal pride, racial discrimination, and to give him a practice - sold him as a slave to a prostitute. After 12 years of service mainly threshing rice, he discovered the one taste of all things, merged space and awareness, and became spiritual teacher to the prostitute as well as to the hundreds of people in that district. Mahasiddha #31

Carbaripa ཙ་རྦ་རི་པ། (Carpati, “The Petrifier”)

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #64

Legends about Carbaripa seem to fit better in the shaman lineage than the buddhist one. These stories could be an example of reinterpretating symbols from a different point of view. From the shamanistic point of view, stories about him turning people to stone imply magic and the power of place. From the buddhist viewpoint, these can be interpreted as a teacher’s ability to disperse disciples discursive thoughts and distractibility, their skill in inspiring the transformative powers of deep meditation. A deeper meaning can be understood in how he liberated people from their petrified social and cultural concepts. The main legend about him describes him helping a young wife abused and beaten by her wealthy husband and his aggressive, controlling mother. The stories don’t describe but pictures of him frequently show him copulating in the sky with this young wife. Mahasiddha #64

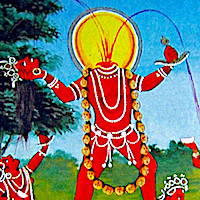

Virupa བི་རཱུ་པ། (“Dakini Master”)

9th century CE

Mahasiddha #3

Though the hero of many miraculous stories of walking on water, making the sun in the sky stop moving, subjugating demons and over-coming Hindu gods; the main symbolism of Virupa’s life revolved around understanding the sense and not just the words, of following a path of moment-to-moment awareness rather than an external set of values, ethics, and discipline. Revered in the Sakya lineage of Tibetan Buddhism as the first lama in the “Journey without Goal School,” he was kicked out of a monastery after living and practicing there for more than 25 because of eating meat and drinking alcohol. The monks soon recognized their mistake and begged him to return but he refused and continued his aimless wondering exemplifying Lao Tzu’s description of wu wei.

Kantalipa ཀནྟ་ལི་པ། ("The Ragman-Tailor")

800 – 900 CE

Mahasiddha #69

Living life on the deep, dark bottom of society as an untouchable and barely surviving with never a full stomach by digging rags out of garbage and sewing the small pieces into cloth; Kantalipa represents how to deal with misery, poverty, and society’s revulsion—not an easy challenge. When he accidentally stabbed himself with a needle and the blood ruined a piece of cloth he had been working on for a long time, Kantalipa hit bottom rolling around on the ground, tearing his hair, and moaning like an animal. “When the student is ready, the teacher arrives” and Kantalipa was ready. He began an intense meditation practice experiencing his needle as mindfulness, the tread as compassion, and the rags as empty space. Mahasiddha #69

Udhilipa ཨུ་དྷི་ལི་པ།

(9th century CE)

The Bird-Man

On an external level, Udhilipa’s story seems very common: an aristocrat with a great fortune meeting a guru, practicing for many years, and finally achieving realization and psychic powers, in this case an ability to fly. Understanding his story in symbolic terms; however, points toward esoteric inner yoga practices including methods of waking up the 8 body mandala centers that divide into 24 cakras and then into a thousand capillary channels. And as we’ve seen in numerous yogic stories of liberation, flying can mean the freedom from conceptual prisons, body identification, and ego-centric illusions.

Nirgunapa ནིརྒུ་ཎ་པ།

(9th century)

"The Enlightened Moron" #57

Born into a low-caste family and inflicted with a moronic lassitude, depression, and such a lack of intelligence and skill that his parents thought it would have been better had he not been born; Nirgunapa sunk into the depths of suffering and despair. While unable to spark even enough motivation to beg for food, a teacher found him in a remote place and gave him enough food to survive. The teacher offered to give him a spiritual practice and Nirgunapa accepted with the condition that he not have to get up off his back. Exemplifying the principle of basic goodness in spite of possessing none of the materialistic qualities valued by society, he became a great teacher. While wandering through villages, when he met someone who asked him a question, he answered only by gazing into their eyes and crying which awoke in them a deep sense of compassion.

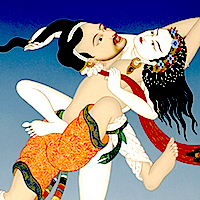

Mekhala མེ་ཁ་ལཱ། (“The Elder Severed-Headed Sister” )

late 9th century

Mahasiddha #66

One of two unmarried, mischievous daughters; Mekhal’s father married her off to an unsuspecting boy from another village. He soon realized though and an intense and constant “battle of the sexes” began. As their lives sunk into more and more misery, the younger sister—Kanakhala—suggested running away to another country. Mekhala, however, realized that their problems were self-created and would follow them wherever they travelled. This realization somehow seems to have triggered an encounter with a famous guru who initiated them onto a spiritual path. After 12 years, they returned to the guru but brought no offerings. According to the story, the guru asked for their heads and they immediately cut them off with “the keen-edged sword of pure awareness.”

Jālandhara ཛཱ་ལནྡྷ་ར་པ། ("The Ḍākinī's Chosen One")

888 CE –

Mahasiddha #46

Jalandhara ཛཱ་ལནྡྷ་ར་པ། “The Ḍākinī's Chosen One” (late 9th century)

Another wealthy and privileged brahmin who saw through the materialistic values of his culture and renounced it to search for a more meaningful life, Jalandhara left everything to live in a cremation ground meditating. Going on to become an important mother-tantra siddha, one of the nine naths, and guru to 10 of the 84 Mahasiddhas; he founded one of the two main nath lineages (A Hindu tradition favored by Kabir that blended Shaivism, Buddhism and Yoga traditions using Hatha Yoga to transform the physical into awakened perception of “absolute reality”), taught practices that unify the male and female forces, dissolve the subject/object dichotomy, and open the non-dual doors of perception. Mahasiddha #46

Kanakhala ཀ་ན་ཁ་ལཱ། ("The Younger Severed-Headed Sister”)

late 9th century

Mahasiddha #67

One of two unmarried, mischievous daughters; Kanakhala’s father married her off to an unsuspecting boy from another village. He soon realized though and an intense and constant “battle of the sexes” began. As their lives sunk into more and more misery, she suggested running away to another country. Mekhala, however, realized that their problems were self-created and would follow them wherever they travelled. This realization somehow seems to have triggered an encounter with a famous guru who initiated them onto a spiritual path. After 12 years, they returned to the guru but brought no offerings. According to the story, the guru asked for their heads and they immediately cut them off with “the keen-edged sword of pure awareness.”

Ajogi ཨ་ཛོ་གི་པ། ("The Rejected Wastrel")

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #26

As a child in a rich family, Ajogi was so fat that his parents had to do everything for him. He wouldn’t even get up to go to the bathroom or eat. When this became too much for his parents they first threatened and then actually abandoned him to cremation grounds in the midst of half-burned bodies and wild animals. Still not willing to get off his back, a wandering wise guru challenged his helplessness strategy - not by trying to make him change but by accepting Ajogi’s situation exactly as it was and working with it. This story and practice gives inspiration and a practical path for the most freakish, despised, and rejected. Mahasiddha #26

Kapālapa ཀ་པཱ་ལ་པ། (“The Skull Bearer”)

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #72

Suicidal and lost in despair after his wife and 5 children died from a plague, Kapalapa met in a cremation grounds Kanhapa who suggested he practice the dharma rather than just die. Making a bowl from his wife’s skull and ornaments from his children’s bones, Kanhapa taught him to see the emptiness of the bones as a creative, fulfillment meditation. After years of practicing in this way, Kapalapa became a great teacher himself helping hundreds of disciples. Mahasiddha #72

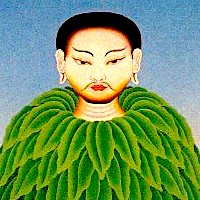

Manibhadra

10th C. CE

One of the 84 Mahasiddhas in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and described as the “Happy Housewife’ siddha” and “Model Wife,” Manibhadra as a teenager met her teacher Kukkuripa and bravely followed him into the cremation grounds where she began practicing Vajrayana. Instead of leaving the conventional world to practice though, she married, had children and brought her spiritual practice into her daily life demonstrating the sacredness and enlightenment in the simple, ordinary world and becoming an exemplar to householders.

Khaḍgapa ཁཌྒ་པ། ("The Fearless Thief")

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #15

Hiding in a cremation ground after a failed robbery, Khadgapa met Carpati, an enlightened yogi and asked for some meditation practices that would make him into an invincible, uncatchable thief. Carpati gave him practices and instructions for finding the “radiant sword of undying awareness.” Khadgapa thought this sword would cut his physical enemies but instead it cut through his real foes: anger, hatred, aversion, desire, greed, sloth and stupidity. In spite of his life of crime, Khadgapa became a great Mahasiddha himself proving that any lifestyle and profession can launch the highest realizations. #15

Dombipa

10th C. CE

Enlightened ruler of Magadha (Kashmir), Dombipa treated all his subjects like a “father would treat his only child” but his country suffered almost endless war, crime, famine, and poverty. He brought back prosperity, peace, and health but when he took a low caste “untouchable” as consort and started drinking large amounts of alcohol, the shocked people forced his abdication. After 12 years when the country’s problems returned, they begged him to return which he did “riding on a pregnant tiger” with his consort. To rule them again, he asked that they abandon the caste system. When they refused he went back into his meditation saying, “My only kingdom is the kingdom of truth.” This lineage continues with the Trungpa Tulkus.

Kukkuripa ཀུ་ཀྐུ་རི་པ། ("The Dog Lover")

915 CE –

Mahasiddha #34

Kukkuripa “The Dog King” ཀུ་ཀྐུ་རི་པ། (10th century CE)

A wandering ascetic, Kukkuripa found and adopted a starving dog brought it back with him to the cave where he lived and meditated. Kukkuripa’s meditation practice took him to pleasurable, psychological god realms but memories of his dog connected him back to the real world where he saw his loyal dog sad, thin, and starving. Spurning the luxury, comfort and extravagance; he returned to the cold, dark, very uncomfortable cave out of compassion for the dog. The dog then became his teacher blending his mind-stream with the deepest insight of all the Buddhas. Naropa sent Marpa to study with him and he became one of Marpa’s most important teachers, famous for his songs of realization, and a “patron saint” for all the downtrodden and oppressed. Mahasiddha #34

Bhikṣanapa བྷི་ཀྵ་ན་པ། ("Siddha Two-Teeth")

940 CE –

Mahasiddha #61

Bhikshanapa བྷི་ཀྵ་ན་པ། “Siddha Two-Teeth” (10th century CE)

Low caste and very poor, Bhikshanapa unexpectedly inherited some wealth. Like most people today winning a lottery or inheriting unaccustomed riches, he quickly lost it all along with his fair-weather friends. This led to a period of intense self-loathing and depression but also an openness to meeting and hearing a teacher and new way of experiencing the world. Seeing through his consumerism andspiritual materialism, he metaphorically (and possibly physically too), lost all but two of his teeth which became symbols for the balance and harmony of wisdom and skillful means. Resuming his external life style of roaming from village to village, he transformed from a miserable, needy beggar only thinking about himself into a wonderful teacher constantly dedicated to helping others. Mahasiddha #61

Dharima

10th century CE

Prostitute, consort of the famous Mahasiddha Tilopa, slave owner and student of Mahasiddha Luipa (probably a different person with same name and profession); Dharima and Tilopa started on this spiritual path together, practiced together for many years, and when enlightened taught together. They learned the "Illusory-body" yoga from Nagarjuna’s tradition, Dream yoga from Caryapa, Cakrasamvara and the Clear Light from Lavapa, and from the woman saint Subhagini, Candalini-yoga and the Hevajra tantra. They forged these 4 traditions into what became the Kagyu lineage of Mahamudra that continues powerfully today through teachers like Chogyam Trungpa and the Karmapas.

Nāropā

955 – 1040 CE

Born a high status Bengali Brahmin, Nāropā became a great debater, scholar, Nalanda abbot, and “Guardian of the Northern gate.” In a famous encounter with his teacher, Tilopa, he realized that he only understood the words of the teachings, not the true sense and began a journey that defines the criteria for lineage holders on this list. An important teacher to many enlightened teachers and mahasiddhas including Atisa, Maitripa, Dombipa, Marpa and many other Tibetans who took these teachings to Tibet where they flourished as they were destroyed in India by an Islamic invasion said to have killed over 400 million people.

Minapa མཱི་ན་པ། (Macchaendra, Matsyendra, "The Hindu Jonah")

10th Century CE

Mahasiddha #8

Bengali fisherman, “India’s Jonah,” a hunter who became the hunted and swallowed by his prey; Minapa unexpectedly and unintentionally heard some highly secret dharma teachings, practiced alone for 12 years and then became a famous mahasiddha and teacher. Protector deity of Nepal, bringer of rain in drought, and original science of yoga teacher; Minapa is also revered in Nepal as the bringer of the first rice seeds. A symbol for the wisdom born in solitude and the journey into deep subconscious depths, he’s know for saying, “What a precious jewel is one’s own mind.”

Dhilipa དྷི་ལི་པ། (“The Epicurean Merchant”)

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #62

Dhilipa had a sesame oil pressing business that did really well and made huge profits. He devoted this wealth to personal pleasure-seeking and is said to have had at each meal 84 main courses, 12 deserts, and 5 kinds of beverages prepared by the best chefs of the time. After one of these sumptuous banquets, a dharma teacher guest questioned him about how far his pleasure seeking was really taking him and pointed out that he could go on making more and more money but it wouldn’t bring him any more true happiness or realization. Like he extracted oil from sesame seeds, Dhilipa then extracted dualistic concepts from experience, realized the union of opposites, and burned the pure flame of awareness. Mahasiddha #62

Goraksa ཤྲཱི་གོ་རཀྵ་ནཱཐ྄། (Nāth Siddha Gorakṣa, "The Immortal Cowherd")

10th Century CE

First haha yoga teacher, founder of India’s largest yoga sect, and non-sectarian Tantric leader; Goraksa assimilated Buddhist insight and understanding into a Hindu context free of duality and integrated tantric practices into Buddhist philosophy. His life symbolizes and his teachings reinforce that every condition and situation people find themselves in has equal potential for realizing the highest awareness. He emphasized the potential in even the most negative circumstances and taught to appreciate everything rather than fighting against our experience and trying to attain a fantasy of what we might think is better.

Vyālipa བྱཱ་ལི་པ། ("The Courtesan's Alchemist")

c. 884 - c. 1044

Mahasiddha #84

Vyalipa བྱཱ་ལི་པ། “The Courtesan's Alchemist (10th century)

After 13 years and the loss of all his wealth, alchemist and searcher for the “elixir of immortality,” Vyalipa gave up his dedicated quest, threw his manual in a river, and becoming a wandering beggar. Later a prostitute who found the book as well as the missing ingredient Vyalipa was unsuccessfully looking for, paid him to renew his quest. They discovered elixir but refused to share it and became imprisoned in a deathless, blissful but empty psychological god realm. According to Taranatha though, Vyalipa later returned to the world, shared the secret elixir with Carpati, and became a famous realization-song singer-songwriter. Mahasiddha 84

Tilopa

988 – 1069 CE

Born a king, Tilopa - like the Buddha - wasn’t that impressed by fame and fortune and left everything to go on a spiritual search. When he met the teacher Nagarjuna though, he was told to return to his kingdom and kingship. He saved his country during a war with non-violence. He later became a monk and scholar but another teacher, Matongha saw pride remaining from his royal caste and advised him to leave, go into the world, and take a job crushing sesame seeds during the day and procuring for a prostitute at night. This led to him becoming a great Mahasiddha, lineage holder and teacher to Naropa.

Kumbharipa ཀུམྦྷ་རི་པ། (“The Eternal Potter”)

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #63

Kumbharipa was a potter bored into despair by the repetition and meaningless tedium of his profession of making pottery. Deeply depressed and on the verge of suicide, he met a teacher who pointed out the universal nature of his unhappiness and suffering. Pointing out the symbolic understanding of the pottery wheel being like the wheel of life, our passions and thoughts being like the clay, and 6 pots being like the 6 realms; Kumbharipa practiced this insight and became enlightened entering a Lao Tzu type wu wei state with the “potter’s wheel spinning by itself and pots spring from is a joy sprang from this potter’s heart.” Mahasiddha #63

Thaganapa

11th C. CE

A low-caste, compulsive liar, Thaganapa’s entire life depended on his lies, deception, and scams. One day he met a monk who saw through, confronted, and challenged him to lead a better life. Thaganapa asked for teachings and the monk gave him a practice of using deception as an antidote to deception teaching him that everyone’s experience is deceiving from the beginning, that everything is a lie. He meditated on this for 7 years and then on all as emptiness until he became enlightened himself and taught a path of resolving paradox and unifying conflict.

Kaṅkaṇa ཀངྐ་ཎ་པ། (“The Siddha-King”)

11th century CE

Mahasiddha #29

A prosperous king addicted to indulging his every whim and desire, Kangkana met a wandering wise man who pointed out how empty his life was - like a mouse on a treadmill chasing imaginary pleasures. Kangkana realized the truth of this but not wanting to abandon his position and kingdom to become an ascetic asked for a practice he could do while remaining a king. This practice taught him the oneness of experience and he transcended the differences between pleasure and pain, loss and gain, stress and strain. Mahasiddha #29

Mekopa མེ་ཀོ་པ། ("Guru Dread-Stare")

1050 CE –

Mahasiddha #43

Mekopa, མེ་ཀོ་པ། Guru Dread-Stare (11th century)

Always cheerful and kind Bengali food merchant taken as a student by a yogin customer, Mekopa saw into the vastness of his own mind, the uselessness of chasing desires, and harmfulness of action based on duality. His realization led him far beyond the limits of status quo, conventional social standards and behavior; into a lifestyle unbound by concern for people’s opinion, wandering about a cremation ground “like a wild animal” and into towns like a mad saint with dreadful, staring eyes. Mahasiddha #43

Machig Labdrön མ་གཅིག་ལབ་སྒྲོན།

1055 – 1149 CE

Nun, mother, wandering yogini, mind Stream emanation (tulku) of Yeshe Tsogyal that later became Jetsun Rinpoche; Machig Labdrön came from a Bön family and blended these shamanistic teachings with Buddhist Dzongchen to develop several Tibetan Vajrayana lineages as well as Mahamudra Chöd—a Prajñāpāramitā practice of “Cutting-Through-the-Ego” and experiencing emptiness. A child protege and scholar at a very early age, she left a comfortable and honored place in a monastery to wander and live with beggars and sleep wherever she found herself. Though criticized for having children, her teaching became so popular they spread from Tibet to India. In Tibet, it’s said she overcame the patriarchal bias of her times and gave teachings to as many as 500,000. Her lineage continues the Mahasiddha tradition of India and the Crazy Wisdom teachings of Tibet.

Koṭālipa ཀོ་ཊཱ་ལི་པ། ("The Peasant Guru")

1084 CE –

Mahasiddha #44

Kotalipa ཀོ་ཊཱ་ལི་པ། “The Peasant Guru” (2nd half of eleventh century)

Jayānanda ཛ་ཡཱ་ནནྡ།། ("Crow Master")

11th - 12th century

Mahasiddha #58

A Tantric Buddhist master practicing in Bengal during a time when Buddhism was illegal, Jayananda was exposed by a jealous neighbor and imprisoned by the anti-Buddhist king. Before being captured though, he had befriended and fed a big flock of crows. In Tibetan culture crows are considered bad omens, capable of bringing great harm, and feared. But in a symbol of tantric transformation, Jayananda had made the crows allies. Then—metaphorically as crows or symbolically as an inclusion of the negative—the king was upended, reduced to hiding under his thrown, and as a consequence became a great and influential siddha himself. Mahasiddha #58

Kālapa ཀཱ་ལ་པ། ("The Handsome Madman")

12th century CE

Mahasiddha #27

So handsome people in the street would stop to stare at him, Kalapa suffered from the paparazzi effect, the stalking and complete loss of privacy. To escape his unwanted fame, he moved into a remote cremation ground where he met an enlightened teacher. This led to his practice of dissolving the delusion of separation between self and other, “uninhibited action,” and communication with people without restraint, political correctness, or concern for praise and blame. Becoming known as a divine madman, he challenged status quo assumptions, prejudice, and belief systems. Last of the traditional 84 Mahasiddhas, Kalapa established the Kalacakra lineage.Mahasiddha #27

Karma Chagme Rinpoche I ཀརྨ་ཆགས་མེད་རཱ་ག་ཨ་སྱས།

1613 – 1678 CE

Considered a more modern-day mahasiddha, an accomplished scholar, and prolific writer who almost became the 9th Karmapa; at the age of 6, Karma Chagme began studying with his tantric siddha father, Pema Wangdrak, and learned magic ceremonies, geomancy, “white” and “black” astrology. He continued studying with the most realized Nyingma and Kagyu masters of his day, learned the entire cycle of Nyingma teachings, and became famous throughout Tibet while traveling for 1.5 years with the 7th Karmapa. He became a master in both the Mahamudra and Dzogchen traditions, devoted himself to Sukhāvatī practice, and became an emanation of "Red Avalokiteśvara.” His lineage continues and the current tülku lives today in the Kathmandu Valley.

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche དིལ་མགོ་མཁྱེན་བརྩེ།

1910 – 1991 CE

"Mind" incarnation of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo

Vajrayana master, poet, terton, scholar, and head of the one of Tibet’s main traditions; Khyentse Rinpoche became a major resource and driving force during Tibetan Buddhism’s transition out its 1000 years of isolation into the rest of the world. A descendent of Tibet’s legendary king, Trisong Detsen and a political minister father; he began an intense meditation practice and religious philosophy training when only 7 years old and then spent 13 years in caves and remote hermitages doing solitary retreats. An “archetype of spiritual teacher” and root teacher to hundreds of Tibet’s young lamas and to most of Tibet’s important modern teachers including Chogyam Trungpa, Dzongsqr Khyentse, the Dalai Lama, and Pema Chödrön; Khyentse Rinpoche’s wisdom and compassion continues to spread throughout the world.

Chögyam Trungpa

1939 – 1987 CE

A once-in-a-generation kind of teacher, a mahasiddha for our times, a transducer transforming ancient wisdom into modern idiom. Per Allen Ginsberg, “A Renaissance man of the highest peaks of East, meditation emperor, space awareness Dance-master, witty rude calligrapher whose poetry and flower arrangements unite the Mind with Body… Prime Minister of Imagination… Chairman of the Board of Directors of Ordinary Mind.” Meditation master, scholar, teacher, poet, artist, he was honored as a mahasiddha by teachers like Khyentse Rinpoche and the 16th Karmapa. “The father of Tibetan Buddhism in the US,” his influence was and remains beyond words.

Mingyur Rinpoche

1975 CE –

Modern-day Mahasiddha

Major Dzogchen and Mahamudra lineage holder, descendant of the Tibetan kings Songtsen Gampo and Trisong Deutsen, abbot of Sherab Ling, and builder of Tergar Monastery; Mngyur Rinpoche left his elevated position in the middle of a 2011 night alone and taking nothing with him. For 4.5 years, he lived as an unknown yogi doing a “wandering retreat” in the Himalayas. He now has centers on 5 continents, teaches extensively, and continues his studies not only of Buddhist philosophy but also Western science and psychology.

Related Sources (0 sources)

Quotes about the Mahasiddha Lineage (3 quotes)

“You are of the ancestral lineage of the gods of clear light, the lineage of the mahasiddhas... therefore, your dream is not deluded.”

Comments: Click to comment

“The Siddhas had rediscovered the direct way of spontaneous awareness and realization of the universal depth-consciousness which had been buried under the masses of scholastic learning, abstract philosophical speculation, hair-splitting arguments and monastic rules”

Comments: Click to comment

“The siddhas' action is not our ordinary action, although it may appear so on the surface. Quite the contrary is true, for their action is styled 'non-action.' Like the Toist concept of wu-wei, it is unmotivated and objectless... all actions have the same value. It is only the prejudices and limitations of the observer's dualistic mind that see one set of actions as harmonious, self-less and 'divine' and another as unconventional, outrageous, or insane.”

Comments: Click to comment

Comments (0)